The Installation Portrait

of Silvia Elena (2008) by Swoon as a Vehicle for Denouncing

Violence and Feminicide in Mexico

You mean you think that Kelly is dead? I yelled. More

or less, he said without losing an ounce of his composure. What do you mean

more or less? I shouted, Either someones dead or they arent dead, damn it! In

Mexico, one can be more or less dead, he answered very seriously.[1]

Roberto

Bolaño, 2666

The phrase kind of dead is drawn

from the novel 2666 by the Chilean

writer Roberto Bolaño. In The Part About

The Crimes[2] (La parte de

los crímenes), it relates the murders of women that take place in the fictional

city of Santa Teresa, as well as the investigations carried out there but that

usually do not lead to any results. The narrative is based

on the feminicides of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico in the

early 1990s. In this essay, I aim to document and analyze how an installation

can create multisensorial spaces that allow English-speaking spectators to reflect

on the issue of feminicide in this

border city.

In

Mexico you can be kind of dead -suspended

between fiction and reality-, because often the bodies of victims are not found

or properly identified, leaving their families in a state of prolonged grief

and uncertainty that can last a lifetime. It is common for people to disappear

and that their bodies be thrown into vacant lots or abandoned in the desert and,

currently in the city, many of these bodies belong to women. In resistance to

the neglect of this social situation, works of art have emerged with the

intention of making this violence visible from different perspectives. One

example is Portrait of Silvia Elena

(2008) by the U.S. artist Caledonia Curry, whose pseudonym is Swoon. The piece

is based on the feminicide

of Silvia Elena Rivera Morales, perpetrated in 1995 in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

The installation Portrait of Silvia Elena was exhibited

from May 30th to June 5th, 2008 at Honey Space Gallery,

located on the West Side Highway between 21st and 22nd Streets

in New York City. This was an old warehouse that was recovered to establish an

independent exhibition space dedicated to presenting artistic work in a

non-commercial environment.[3]

The site was left intentionally in its existing state and the condition for the

exhibition was that the artist's proposal had to be adapted to its spatial

characteristics. The gallery functioned without staff, during the day the space

was open to the public, the entrance was free, and there was no surveillance or

restriction for the spectators.

The installation was designed in

such a way that the audience had active participation and absolute liberty to appropriate

the piece and intervene the space. We should bear in mind that the word public has its origin in belonging to the people[4] and in this

sense, the group of people who visited the exhibition stopped being mere

spectators and became active subjects who formed a part of the democratic

politics of the place.

An important aspect was that,

although the installation was mounted in an alternative space without rules or

curatorial protocols, the artist included texts and indications in English that

guided the viewer with instructions that she herself determined. In the entrance

hall of the gallery the title Portrait of

Silvia Elena (Fig.1) was presented with black letters on a turquoise

background combined with white tones, and on its side was a woodblock engraved

with the face of the young woman, flowers and candles. There were also

photographs of Silvia Elena and other women who had been murdered or had

disappeared, and photocopies of flyers regarding the search for these women

issued by the Procuraduría General de la República, the Mexican government office that coordinates

the investigation of crimes.

1 Swoon, Portrait of Silvia Elena, 2008,

installation, details, Honey Space Gallery, NY, (photography by Swoon).

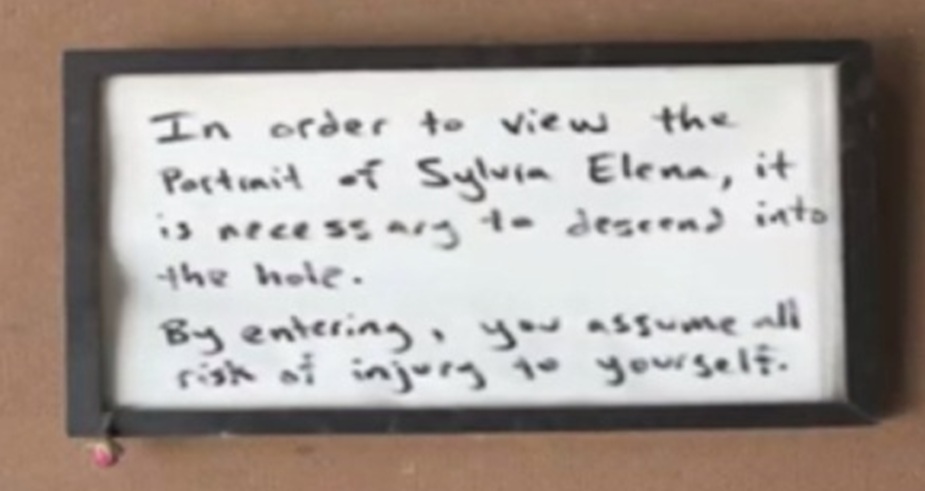

On the left side of

the entrance hall, there was a small frame (Fig. 2) that included the following

text:

In order to

view the Portrait of Sylvia Elena, it is necessary to descend into the hole.

By entering,

you assume all risk of injury to yourself.

2 Swoon, Portrait of Silvia Elena,

2008, installation, details, Honey Space Gallery, NY, (photography by Swoon).

In the installation space, it

was necessary to descend through a hole and a staircase to visit the work. The

proposal was a guided tour with an evident quality of a symbolic ritual that augmented

as one went down and slowly entered the installation environment. The public saw,

felt and breathed a considerable amount of debris and dust. As the days passed,

a putrid smell from the flowers and water became increasingly notable, as they were

not changed during the time the installation lasted. It was a dim area where

only a few candles located in different parts of the space served as

illumination, and there were days when the candles were out and the lighting

came only from the entrance hole. On one of the walls of this basement area the

mural Portrait of Silvia Elena

(Fig.3) was located.

3. Swoon, Portrait of Silvia Elena, 2008, installation,

detail of the interior view, Honey Space Gallery, NY, (photography of Swoon).

Inside, the visitors

could hear an ambient audio of Silvia Elenas mothers voice:

Well, theres

my daughter, her remains. We came and took the dirt off of her. But when we came

back, it was all filled up again. Well, who knows how this happened to my

daughter. I cant understand how this has happened to so many girls. When they came

to tell me that they had found her, well I went and identified my daughter. The

authorities took me to identify her, but my daughter was, there was only the,

just the skeleton. My daughter didnt have flesh anymore. She was just a skeleton.

She was whole, but they must have put something on her face, because all her

flesh was stuck to the bone. It was just the face that didnt have any flesh. I

found her naked, my daughter had no clothes on. Its very sad, and I tell you,

ever since she left, we talk about her all the time at home. All the time. A

day never goes by when we dont mention Elena. We think about her all the time and

we talk about her.[5]

The narration was

recorded at Silvia Elenas graveside while her mother removed the plants that

had grown over it with a metal spoon, sounds that are recorded in the audio.

From the perspective of Swoon and her collaborator Tennessee Watson, the need

to include the audio was based on the search for different narrative layers:

affect, memory, and the testimony that tells a truth from an intimate-personal

viewpoint. As an aesthetic strategy, the elements that are included in the

installation can be associated with the Freudian concept of the sinister, also

understood as "the disquieting strangeness" or "the

ominous". Sigmund Freud defines the sinister as "that uncanny element

that subtly transforms known and familiar things".[6]

That is, what is familiar, in certain scenarios, can become sinister.

This category functions as a

device that brings to the present something reminiscent of the traumatic past.

When experiencing the work, the viewer comes to know a social situation through

a particular case that produces discomfort. The observer, upon entering the

basement with the installation and hearing the words of Ramona, becomes a

witness to the finding of the body of the young woman, and the repetition of

the audio intensifies this feeling of anguish that is produced by the

contemplation of the aesthetic forms of the sinister. This unsettling experience

is interrelated with various dimensions of memory: the testimonial dimension of

the mother who witnessed the tragedy; the dimension of the artist whomakes aesthetic and political use of that testimony and the dimension of the

collective memory of those who know the work and the motive for its creation.

In general, the spectators had a disquieting experience that at the same

time awoke their sympathy with the victim represented; the reactions varied in

relation to the different nationalities of the audience. The Mexicans related

the flowers, the photographs and the candles with an altar for the Day of the Dead.

On the other hand, the New York public interpreted the work through the

translations, and carried out actions that confirmed their identification with

the people portrayed. Some of them returned to place more candles, money, and texts

in Spanish. One of these says, "I had nothing else to leave, so I left this." (Fig.4) Therefore, the work

was transformed with the passage of time. The sensorial elements of the

installation facilitated its aesthetic activation by the viewers. Firstly, they

came to know Silvias case and the situation regarding feminicides

in Mexico, and secondly, through the objects that they placed in the

installation, they showed solidarity with the problems occuring

on the border with Mexico that also involve the United States.

4. Swoon, Portrait of Silvia Elena, 2008, installation,

interior detail, messages and candles left by the visitors, Honey Space

Gallery, NY, (photography by Swoon).

With respect to the

installation, the artist has commented:

In the first two

exhibits in San Francisco and New York, I was simply motivated to share the piece

as widely as possible. These are two of our largest cities, and this is a story

that I believe, as was my case, Americans need to know in order to understand the

problems on our borders that are also a result of our drug trade. This is

something that is also ours, even though we try to leave it "on the other

side of the border". When people hear the story (of Silvia Elena) they are

horrified but dont know what to do. Some ask if the girls were prostitutes, as

if that could explain their deaths. This is another way of trying to keep this

horrible situation "on the other side", so that people continue to

believe that their "normal" lives are safe from such inequality.[7]

The relation Swoon establishes

between feminicides

and the drug trade draws on one of the research

hypotheses that has been raised about these events. It is estimated that

criminal groups in Mexico have complex structures that arise from other

criminal groups. If a group is mainly dedicated to drug trafficking, there may

be members who in turn commit other crimes such as human trafficking,

kidnapping, homicide, and extortion, to name a few.[8]

These convergences and the resulting social problems have been studied by

journalists, academics, international organizations, and artists.

As part of the installation's artistic narrative that sought to make the

events visible, Swoon included photographs related to personal and emotional

aspects of Silvia Elenas life. She was portrayed at her fifteenth birthday celebration,

in her room and with family members. Silvia's personal effects, notes, a mirror

and a comb were also included, objects that referred to her intimate context

and her body, and that--along with the putrid odor of the flowers and water that

referenced the deterioration of organic elements-- established a link between

matter and the event on which the work is based (Fig.5).

5. Swoon, Portrait of Silvia Elena, 2008, installation,

detail, Honey Space Gallery, NY, (photography by Swoon).

The

creative process of Portrait of Silvia

Elena included research through the organization Cuidad Juárez Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa, A.C.,

and the artist maintained a close relationship to the families of the victims

of forced disappearances and feminicides. This

artistic practice linked to memory, the absence of justice and the activism of

the families of the victims reveals the different levels of mourning that,

together, highlight the complexity of the issues of feminicide

and intentional homicide. The personal process of mourning experienced by the

victims families is brought into the public sphere through the materiality of

the work, the artistic strategy of its reproduction and exhibition in a shared space,

its visibilization through the image, and the evocation and representation of

the absent person.

With respect to the representation of loss or absence, the wall that supports

the work can be understood as refering to duelo, which

means both mourning and duel in Spanish, in a double sense: mourning as a

connection elaborated through melancholy and a duel as a versus, in which the player turns around and directly observes

their opponent: the conflict alluded to by the elements on the wall and the

tension it constructs with its observer. The relation between presence and

absence through re-presentation is also related to the proposals of the French

philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy (1940), for whom representation is not a reiteration

but rather than an enhancement of presentation. The work also establishes a

relationship between re-presentation and re-production, in which the former invokes

both presence and absence through the image and the latter refers to the image as

a material, physical trace.[9]

In order to create works that dealt with the memory of social trauma,

Swoon developed creative processes that involved traveling to the scene of the

crime, interviews with the victims families, and direct contact with the

vestiges and personal possessions of the victim. So, as an artist, she also documents and

bears witness to the pain of others.[10]

In keeping with the views of Ileana Diéguez, and

taking into account the notion of afterlife

as conceived by Aby Warburg y taken up by Georges Didi-Huberman, what

shapes the memory of the images are the different densities of experience that

they embody as traces of past lives, of what was and is no longer. Their afterlife refers, as well, to the accumulation

of experience through time, through multiple events in the past, and the vital

residues that are compressed in and communicated through the works.[11]

In the feminicides[12] perpetrated throughout Mexico, the female body has gone through

different violent interventions: sexual torture, mutilations, lacerations,

beatings, or impalements. Some women were even subjected to rituals that utilized

their blood, some had their nipples mutilated by being bitten while they were

still alive, and others had a triangular piece of skin cut out. [13]

In other words, the body was treated as a pile of meat. [14]

These rituals based on suffering, for whatever reason, leave marks or transform

the body: the body is a memory. [15]

In the theories advanced by the Hindu anthropologist Veena Das (1945), the

situations in which the body expresses tension or trauma developed in social

circumstances of excess or abnormality, reveal pain as a socially constructed

reality designed to exert control, and produce a social code: pain as a means

through which society establishes ownership over individuals and through

which it represents the historical

damage that has been done to a person that sometimes takes the form of a

description of individual symptoms, and in other cases that of a memory

inscribed in the body.[16]

In these circumstances, the difficulties for processing pain and mourning

become complicated by the classist-racist-patriarchal regime and the lack of justice. Ramona, Silvias mother,

commented that after looking for her daughter and waiting up for her, the next

day my son and husband went

and filed a report right away. But no, the police

said no right away, that maybe my daughter had left with some boy, that they

were going to wait 72 hours. When her family returned to the authorities, they

again said, no, nothing, that they hadnt found her. Then, my son made a

thousand flyers

and he went out every night, putting up flyers on the roads, in

stores, in restaurants

and she was nowhere to be found, as if the earth had

swallowed her up. Ramona remembers the officials saying, Maam, we have made excellent

investigations. We dont tell you anything because then

you talk, and everything rebounds. [17]

In these commentaries that Silvias mother remembers, it is clear that the

judicial process is subordinated to gender prejudice, to a view that the womens

talk hampers judicial actions. To the date, no one has been accused in Silvias

case.

Given this situation, art can be a pathway for denunciation and greater social

awareness. The multisensorial images that were a part of the installation and

the artists aesthetic strategy allow us to understand the impact on the

audience of this information about the violent and discriminatory events occurring

in Mexico. The reactions were primarily of empathy, possibly because the work didnt

refer explicitly to violence. In the exhibit in the United States, the artist

sought to raise awareness regarding the issues that involved both nations as a

result of their common border.

Bibliography

Bolaño,

Roberto. 2005. 2666. Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz.

Deutsche,

Rosalyn. 2007. Público, en Conferencia

en el curso Ideas recibidas. Un vocabulario para la cultura artística

contemporánea, Museu d' Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), 19 de

noviembre.

Diéguez, Ileana. 2016. Cuerpos sin duelo, iconografías y teatralidades del dolor. México:

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León.

Freud, Sigmund. 2007. Obras completas. Tomo 6. (1914-1917). Madrid: Editorial Biblioteca

Nueva.

González, Sergio. 2002. El hombre sin cabeza. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Monraez, Julia Estela. 2009. Trama de una injusticia: feminicidio sexual

sistémico en Ciudad Juárez. México: Porrúa.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2006. La representación prohibida. Seguido de La

Shoah, un sopolo. Madrid: Amorrortu.

[1] Roberto Bolaño, 2666. (New York: Vintage Spanish, 2017). ¿Quiere decir que cree que Kelly está muerta?, le grité. Más o menos, dijo sin perder un ápice de compostura. ¿Cómo que más o menos?, grité. ¡O se está muerto o no se está muerto, chingados! En México uno puede estar más o menos muerto, me contestó muy seriamente.

[2] A second fragment of The Part About The Crimes,

reads: This happened in 1993. January 1993. Beginning with this death, people

began counting the murders of women. But it is likely that there were others

before this one. The first victim went by the name of Esperanza Gómez Saldaña and was thirteen

years old. But its likely that she wasnt the first one. Maybe out of

convenience, since she was the first victim of assassination in 1993, she was

at the top of the list. Even though surely

there were others who had died in 1992. Others who were left off of the list,

or who were never found, buried in mass graves in the desert or whose ashes

were scattered in the middle of the night, when not even those who sow them

know where, in what place they can be found.

[3] The building was demolished

in 2012 and to date the gallery has not been relocated.

[4]Rosalyn Deutsche, Público, (lecture presented in the course Ideas recibidas. Un vocabulario para la cultura artística contemporánea, in the Museu d´Art Contemporani de Barcelona-MACBA).

.

[5] The following video, includes an audio and some photos from the

installation in the Yerbabuena

Center for the Arts in San Francisco and the Honey Space Gallery in New York: https://vimeo.com/16091975,

(consulted April 2nd, 2017).

Pos ahí ta mi hija, sus restos, así venimos y le quitamos la tierra. No, ya cuando venimos otra vez ya está bien lleno otra vez. Pos quien sabe cómo le pasaría a mi hija eso. No me explico ni a tanta chica que le ha pasado. Cuando me fueron a decir que ya la habían encontrado pos este si fui y la reconocí a mi hija, me llevaron las autoridades a reconocerla, pero ya mi hija ya, ya estaba la, la pura calavera, ya no tenía carne mi hija ya, ya era la pura calavera. Estaba toda enterita, no más, yo digo que le pusieron algo en su cara, porque ella tenía toda su carne pegada en, en el hueso toda, nomás la cara era la que no tenía carne. La encontré desnuda, no tenía nada mi hija, de ropa. Es muy triste, y viera que desde que se fue ella todo el tiempo ahí en la casa hablamos de ella, todo el tiempo nunca la nos dejamos que digamos ora no mencionamos a Helena, todo el tiempo se nos viene a la mente y hablamos de ella.

[6] Sigmund Freud, Lo siniestro, in Obras completas, (Madrid: Biblioteca

Nueva, 1981), 2484.

[7] This interview is a result of my

research residency in New York from June 15 to September 15, 2017.

[8]See Salvador Bernabéu, Carmen Mena coords., El feminicidio de Ciudad Juárez.

Repercusiones legales y culturales de la impunidad, (Andalucía: Universidad

Internacional de Andalucía, 2012).

[9] See Jean Luc-Nancy, La representación prohibida: seguido de La Shoah, un soplo. (Madrid: Amorrortu Editores, 2006.).

[10]

Ileana Diéguez, Cuerpos sin duelo,

iconografías y teatralidades del dolor. (México: Universidad Autónoma de

Nuevo León, 2016.) 353.

[11]

Ileana Diéguez, Cuerpos sin duelo, iconografías

y teatralidades del dolor, 353.

[12] The Federal Criminal Code of

Mexico in its Article 325 specifies that: the crime of feminicide

is considered to be committed when a woman is deprived of life for reasons of

gender. It is considered that there are reasons of gender when any of the

following circumstances occur: I. The victim shows signs of sexual violence of

any kind; II. The victim has been inflicted with unusual or degrading injuries

or mutilations, prior or subsequently to the deprivation of life or acts of

necrophilia; III. There are antecedents or background data of any type registering

violence of the active subject against the victim in the family, work or school

environment; IV. There has been a sentimental, affective or trusting

relationship between the active subject and the victim; V. There are data that

establish that there were threats related to the criminal act, harassment or

injury by the active subject against the victim; VI. The victim has been held

incommunicado, at any time prior to the deprivation of life; VII. The body of

the victim has been exposed or displayed in a public place. The subject who

commits the crime of feminicide will be sentenced to forty

to sixty years in prison and charged with a five hundred to thousand day fine.

In addition to the sanctions described in this article, the active subject will

lose all rights in relation to the victim, including those of succession. If

the feminicide is not proven, the rules of homicide

will apply. In addition: The public servant who maliciously or negligently

delays or hinders the process or administration of justice will be imposed a

prison sentence of three to eight years and a five hundred to fifteen hundred

day fine and will also be dismissed and disqualified for three to ten years for

any public job, position or commission. See: Comisión

Nacional de Derechos

Humanos, available at:

http://www.cndh.org.mx/sites/all/doc/programas/mujer/6_MonitoreoLegislacion/6.0/19_DelitoFeminicidio_2015dic.pdf,

(accessed March 2, 2018 ).

[13] Sergio González. El hombre sin cabeza. (Barcelona: Anagram, 2002), 22.

[14] Ileana Diéguez, Cuerpos sin duelo, iconografías y

teatralidades del dolor, 201.

[15] Ileana Diéguez, Cuerpos sin duelo, iconografías y

teatralidades del dolor, 209.

[16] Veena Das, Sujetos de dolor, agentes de dignidad. (Bogota: Ed. Francisco A. Ortega, 2008) 411.

[17] Interview in: Julia Estela Monárrez. Trama de una injusticia: feminicidio sexual sistémico en Ciudad Juárez, (México: Porrúa, 2009) 157-158.