The Multidimensional and the Multiple in Contemporary Art

Let's Sow Dreams, Let's Harvest Hope[1] (2015-2018) by Lapiztola Stencil

Currently, it is common for artists

to implement aesthetic strategies that expand the scope of

the discourse of

their artistic work. Some resources used for this purpose are the multiplication

and fragmentation of the image, that represent a constant process of reconfiguration

and resignification. The work Let's Sow Dreams,

Let's Harvest Hope (2015-2018) by the Mexican collective Lapiztola Stencil,

formed by Rosario Martínez, Roberto Vega and Yankel Balderas, is a piece that

was initially a stenciled mural; however, between 2015 and 2018 it has been transposed

into multiple formats: murals with variations, digital animation, images that

circulate on social networks, and commercial objects. This reproduction in

different spaces and dimensions has modified the works meaning, and even led

to alternative readings of the first version of the piece. In this essay, I

propose to analyze the implications of the multiplication and fragmentation of

the image that circulates in public spaces.

To

begin with, it is necessary to ask: What are the limits of reproducibility of

the image without significantly modifying its aesthetics and meaning? I have

chosen to call these manifestations multidimensional images, that is, images

that undergo transformations from the formats in which they were originally conceived and, as a

result, transformations in their

meaning.

Let's Sow Dreams, Let's Harvest Hope (Fig. 1) was

first created in 2015 on the exterior wall of the Museum of Popular Arts Belber

Jiménez in Oaxaca, Mexico. The mural presents a figurative

portrait in black and white of a girl. Her gaze is directed to a point just

over the horizon. She is seated on orange, pink and light blue flowers. She

holds a red heart in her hands from which three red flowers sprout. The piece

also includes a fragment from a speech given by the Oaxacan

activist Beatriz Cariño Trujillo, who murdered in 2010:

Brothers,

sisters, let us open our hearts like a flower waiting for the first ray of

sunlight in the morning. Let us sow dreams and harvest hopes, remembering that we

can only build from the bottom up, from the left, and from the heart.[2]

1.

Lapiztola Stencil, Let's Sow Dreams, Let's Harvest Hope,

2015, mural made with stencil and direct painting, detail, exterior wall of the

Belber Jiménez Museum, Centro, Oaxaca (photography by

Lapiztola Stencil).

The

image in the piece was also reproduced on screen-printed objects on the

collectives website, as a mural in the Coachella Walls Urban Art Festival in California (2016), as a mural in the Institute of Graphic Arts in

Oaxaca (2017), as a mural in Hanger

Street, Orlando (2017) and as a digital animation (2018). In this latter format

it was circulated through the social

networks of the artists as electoral propaganda to collect signatures for the

independent candidacy for the Mexican presidency of María de Jesus Patricio Martinez,

better known as Marichuy. In this way, the intentionality of the work was constantly

transformed, making evident the complexity of reproducible political art that

circulates in the collective imaginary and the public domain.

In analyzing the strategies

that come into play in the multidimensionality and multiplicity of Let's Sow Dreams,

Let's Harvest Hope, it is pertinent to distinguish

between the walls where the interventions were made, the social networks as a

scenario for the distribution of animation, and the reproductions made on commercial

objects.

Interventions

on walls

In the first intervention in Oaxaca,

Bety Cariños phrase was a key element, since the text is closely related to the

symbols in the work. The heart can be interpreted as a rebirth of tomorrow,

inviting everyone to build it through solidarity, from the bottom to the

left, words related to social sectors committed to struggle and resistance, and from

the heart, on the basis of empathy for one another.

The intense blue contrasts with the black and

white image, establishing a bond of local identity since among the Oaxacan

indigenous groups this tonality is frequently used in textiles and handicrafts. In addition, in western Christian culture, this color in

its various tonalities has been used to represent the Virgins mantle, relating it to divinity and purity.

Similarly, portraits of children remit to innocence and purity (Fig. 2).

2 Lapiztola

Stencil, Let's Sow Dreams, Let's Harvest Hope, 2015,

wall intervention, detail, Historical Center, Oaxaca, (photograph by Lapiztola Stencil).

The mural was erased by the

municipality, and the wall was painted blue again. Following this, there were

anonymous reactions by members of the community that expanded the aesthetic

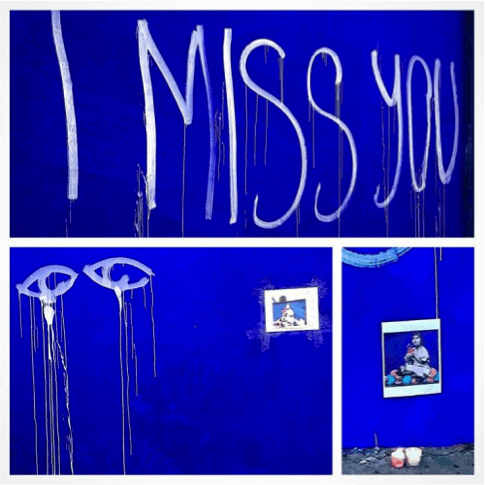

meaning of that wall space. A few days after the murals elimination, the

phrase I MISS YOU appeared on the wall, together with a painting of two white

crying eyes, a color print on letter-size paper of the original mural, and a

couple of candles on the floor (Fig. 3).

3 Paintings that emerged after the elimination of the mural, 2015,

(photograph by Lapiztola Stencil).

To date there are no records

of how long these interventions lasted, but it is evident that the initial image

was so significant for some viewers that, faced with its erasure, they decided

to transform the space into a site of remembrance of the image. Together, the

wall paintings, the photograph of the mural and the candles are similar to a

Mexican altar.

These social phenomena opened up

other possibilities of reproduction of the print in public spaces, and questions

arose like: What are its limits and what is the effect of its temporary

exposure? What determines the reactions of its spectators, particularly in this

case when there no specific mediation strategies are deployed between the

artists and the audience? The realization that the presentation of an image can

have consequences introduces us to its political dimension. Mouffe proposes

that any art work or artistic practice possesses this dimension inasmuch as it

plays a role in the constitution and maintenance, or the critique, of an

existing symbolic order.[3]

The reproduction titled American

Woman (Fig. 4), was created in 2016 in the context of the Coachella Walls Urban Art Festival in California and

used the same stencil matrix as Let's Sow

Dreams, Let's Harvest Hope. The portrait of the girl was presented as a

mirror-image, that is, there were two portraits that were produced by the same

template using it forwards and backwards.

For this reason, in the mural, one image of the girl was turning to the right and the other to the left. They were on a

red background, and in each lower corner,

there were two pink flowers and a green one. Cariños phrase was not

included and instead the fabric of the dress

was extended. The red color was essential to the composition, not only because

it contrasted with the black figures, but because it was associated with blood,

war, passion, and strength. It was not

coincidental that the artists chose to highlight this color for the repetition

of the piece in the United States, where there have been many cases of abuse of

migrant communities. Both the title and the components of the image invite its reading

as a revindication of the indigenous communities and the new generations that

live there.

In the location where the work was exhibited, it was logical for the

public to relate the image to Chicano and Mexican

culture through the iconographic elements of the heart and the indigenous dress

of the person portrayed. It was a highly narrative mural that appealed to

popular imaginaries and affects, generating sensorial experiences in some of

its visitors. Maria Venegas and Cristina Venegas, daughters of Mexican immigrants

who have undocumented relatives in the United States, referred to the work as

"a painting that, through its colors and clothing, reminds us of village

festivities. It is important to show these types of things so that the güeros[4] can know our culture." [5] The relationship that some viewers established between the visual

characteristics of the work, memory and references to Mexican culture can be

related to the search for identity in children of migrants.

4. Lapiztola

Stencil, American Woman, 2016,

intervention on wall with stencil and direct paint, Coachella, California,

(photograph by Lapiztola Stencil).

Another reproduction took place at

the Institute of Graphic Arts in Oaxaca (IAGO) (2016) (Fig. 5). It was placed

in the courtyard as part of the retrospective exhibit Corte Aquí (Cut Here), which celebrated

ten years of artistic production by the collective. A spectator who stood in

front of the wall could perceive the complete vertical image that required the

viewer to gaze upward in order to obtain appreciate it fully.

Roland Barthes, in his reflections on walls and advertising, highlighted

the relationship of the body with the image observed, pointing out that:

A standing image is measured in relation to my own height, and is perceived

through movement rather than through vision. The figures it represents have a

superhuman dimension. The verticality gives them a kind of ambiguous, benevolent

and threatening tone. The wall is both an obstacle and a support, a screen that

both hides and receives, a space where we stop and project ourselves. [6]

The viewers had close interactions with the piece, which they could even

touch. They posed for photographs in front of it, positioning themselves in

relation to the painted figures. The space invited this type of interaction since

the IAGO patio has tables and chairs available for visitors. Some of the users

shared their photos on social networks along with their opinion of the mural.

5. Visitor in the IAGO posing with the

mural, 2017, (photograph from Instagram).

Another reproduction of Let's Sow Dreams,

Let's Harvest Hope was created at Hanger Street, Orlando in 2017. The

stencil included an intervention by the Chicana

artist Liseth Amaya, originally from Los Angeles,

California. Her production has focused on oil painting, watercolor, and ink

drawings, and her principal themes are representations of women and Mexican

communities. The collaborative mural was on a white background on which a large

red circle was drawn, over which the black and white portrait of the girl

holding the heart was set. A chain of blue and red flowers with leaves in black

and white line drawing that followed the shape of the circle was made by Liseth (Fig.6).

6. Lapiztola

Stencil y Liseth Amaya, Let's Sow Dreams,

Let's Harvest Hope, 2017, intervention on wall with stencil and direct

paint, Orlando, Florida, (photograph from Instagram).

Presenting this piece in some cities

in the U.S. implied some challenges since there is a certain visual emphasis in the country on a Chicano

mural aesthetic that appropriates Mexican

icons and symbols to create a new language. Lapiztola Stencil and Liseth Amaya employed

symbols related to Oaxacan communities, but they reconfigured them to represent

the whole community through their subject matter; elements like the heart or

the flowers werent put aside, but integrated into the new narrative and visual

composition.

Reviewing

the different reproductions of Let's Sow Dreams,

Let's Harvest Hope, it is evident that the portrait was

the central element of the piece, using gender and realism to facilitate the spectators identification with the other, as the

representation of the subject, particularly her face and its expression,

reflects the spirit of the person. In addition, the dimensions of the

composition were a key factor, since the template of the figure measured just

over two meters in height.

The later reproductions show significant

changes in the use of color, transforming the perception and symbolism of the

portrait. When it was presented on a white background, it became integrated

with the contiguous walls. It took on a dramatic tone when the background was blue or red, since these primary colors have a symbolic weight of their own.

Another differentiating aspect was the

inclusion or omission of Cariños text. It was present

only in the pieces created in Oaxaca, where it had particular relevance because

the work was designed for a local audience. In the murals in the US, the space originally

allotted to the text was used to extend

the girls dress. If one observes it in

detail, when the text is absent, this part of the image seems somewhat empty, suggesting

that the composition was designed to include it. The advantage of working with a

matrix and reproducible media lies in the possibility of modifying the image in accordance with varied aesthetic

needs.

Animated

prints: from the wall to likes

On January 2, 2018, with the

launching of an animated version of the mural Let's Sow Dreams, Let's Harvest Hope, the paradigm of

reproducibility of the print was transformed. Digital experimentation allowed

the distribution of the image in another dimension of the public sphere: social

networks.

On collectives official

Facebook account that had 16,161 followers, they published the hashtags #porlavisibilidaddelospueblosindigenas[7] #votapormarichuy[8] Marichuy is a Nahuatl woman from Jalisco who wants your signature to

become the first indigenous independent candidate (spokesperson) for the

Mexican presidency in the 2018 elections[9]; and on their Instagram, with

18,400 followers, they published: The time for the peoples emergence has come

#marichuy #signforthevisibilityofindigenouspeoples #ourfightisforlifeletssowdreamsandharvesthope.[10]

Along with the hashtags, a

44-second animation[11] was included, which used the image of the first mural with a blue

background as a reference. The framing was of the girls face and hands with an animation of the movement of the

flowers as they emerge from the heart. Surely, the artists used this version of

the mural because it grew in popularity in

Oaxaca after it was deleted, and they received many expressions of support from

their followers. From an artistic point

of view, the color blue is common in the popular art of Oaxaca, which may have

been another reason to animate this version of the mural.

In the animation, the girl sings Huecanías (Im Going Far),[12] a love song in the Nahuatl

language, originally from Xoxocotla in the state of Morelos, México. The piece

is interpreted by a twelve-year-old girl, and the lyrics and translation are

the following:

|

Huecanías hueca hueca tlalli hunamo nicani, xoxoca tinemis mo-pampa tica nia nitemolompa nomiquilis teuis no yol Xihuala, xihuala notlasontsin, noalimantzin yoloxochitl ompaqui cuica cerca nomiquilis teuis noyol. |

Im going far, To distant lands, Where I can bemoan My mischance. Ill follow you, where you

dont know, Yes, sweetheart. Sweetheart come, pampered, spoiled. Heart, flower, Here I carry you Inside my soul, Yes, sweetheart.[13] |

At the end of the song, the screen goes

black and animated letters read: FIRMA X CHUY[14].

Unlike the reproductions on walls,

the animated version of this piece was designed specifically as a political

advertisement, inviting the followers on social media to sign in support of the

independent candidacy of Maria de Jesus Patricio, spokesperson of the

Indigenous Government Council, as a candidate for the Mexican presidency.

As of March 2018, there were 895

reproductions of the animation on Facebook and 3,745 on Instagram. In this way,

the work entered a complex process of reproduction that moved from the murals

and their digitalization and animation to the direct reproduction of the

animation by users who shared the publication, taking the image far beyond the

era of technical reproduction that Walter Benjamin studied.

Today, Benjamins idea that technical reproducibility modifies the

relationship between the masses and art has expanded and become more complex. Now

that the image has entered the digital era, its circulation is uncontrolled,

and it can be reproduced by anyone with an immediate effect, its meaning is

constantly being reconfigured. The work may lose its original intention and be

subordinated to the objectives of the Internet user who appropriates images and

assigns new meanings to them. Images can be viewed, shared and edited wherever

there is access to the Internet. Moreover, a new interaction with art emerges

when users portray themselves with the images, sharing their opinions and sensory experiences, and on occasion debating them with others on

their social networks.

With these reproductions, the democratization of political art takes on a

new character. Multiple forms of reproduction are intertwined, including those

of public space, the studio, galleries,

museums, and the reproduction done by users through digital media, thus opening

up new frontiers for the study of the phenomenon of reproducibility from

traditional media to technological means.

Objects

produced with impressions of the work Lets

Sow Dreams, Lets Harvest Hope

The image of Lets Sow Dreams, Lets Harvest Hope also circulated on bags and silkscreened

T´-shirts (Fig.7), which were sold through

social media, small businesses in Oaxaca, and a distributor of Mexican products

in Barcelona. The silkscreened images corresponded to the first stenciled mural

that included Beatriz Cariños phrase, with

variations in background color depending on the bag or shirt.

7. Lapiztola

Stencil, Lets Sow Dreams, Lets Harvest Hope,

2017, silkscreened bags, (photograph by Lapiztola Stencil).

The

hashtags of the reproductions of Lets Sow

Dreams, Lets Harvest Hope generate relationships on the web between images

linked to the piece that allow us

to see a sequence that moves from the mural from Orlando, someone posing with a

T-shirt, the animation in support of Marichuy, the image of I MISS YOU after

the censorship of the piece, and the mural in Coachella to the collective in the

process of creation. This installation configured by social network accounts reveals

the ways in which the images penetrate public space and are resignified.

Conclusions

In reviewing the reproductions of Lets

Sow Dreams, Lets Harvest Hope, we can conclude that, when they were

exhibited on walls, the permanence and participation of the viewers were

subject to the social and cultural context of their exhibition. The question

that emerges is then: what were the aesthetic strategies that allowed for the

transformation of that original situation? I imagine that the artists did not foresee

the phenomenon that would arise on the basis of the initial mural in Oaxaca.

The artists produced an initial transformation of public space, and when the

mural was eliminated, their public decided to intervene. In other

reproductions, the audience interacted with the pieces, documented them and disseminated

the images on their social networks. In this way, the murals entered the

digital sphere, expanding the dimensions of the work.

Another variation that can be observed is that the piece went from being

an artistic object to a vehicle of political and commercial propaganda, a process which led to its adaptation. To a

certain extent, the animation in support of Marichuy was compatible with the declaration

of the artists in favor of the visibilization of indigenous communities. With

respect to the commercial uses of the image, the question arises as to whether

political art has the same effect when it can be bought and sold. In this case,

some of the people who purchased the bags and shirts didnt refer directly to

the meaning of the mural in their social networks, but by adding the hashtag #sembremossueñoscosechemosesperanzas

(Lets Sow Dreams, Lets Harvest Hope) one

could browse the Web, see images from other

reproductions and relate their meaning.

Reproduction in public spaces shows

that reproducible art has no limits. The work can have different readings in accordance

with its material or discursive changes, distinct social contexts, and the reappropriations performed

by its audience, and in this way, a new

democratization of multiple images is generated.

Barthes, Roland 2002. La Torre Eiffel. Textos sobre la imagen. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Mouffe, Chantal. 2014.

Agonística, pensar el mundo políticamente. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

______________. 2007. Prácticas

artísticas y democracia agonística. Barcelona: Museu d'Art Contemporani,

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

[1] Sembremos

sueños cosechemos esperanzas

[2] Hermanos, hermanas, abramos el corazón

como una flor que espera el rayo del sol por las mañanas, sembremos sueños y

cosechemos esperanzas, recordando que esa construcción sólo se puede hacer

abajo, a la izquierda y del lado del corazón.

[3] Mouffe, Agonística, pensar el mundo políticamente, (Buenos Aires: FCE,

2014),98.

[4] White-skinned

American people

[5]

Interview in Los Ángeles, California in December

2017. On the basis of a photograph of the murals that I found in Instagram, I

contacted María and Cristina Venegas, who agreed to be interviewed.

[6] Roland Barthes, La Torre Eiffel. Textos sobre la imagen, (Buenos Aires: Paidós,

2002), 98.

[7] For the visibility

of indigenous peoples

[8] Vote for Marichuy

[9] The official

account on Facebook is Lapiztola Stencil and in Instagram

Lapiztola.

[10] llegó la hora del florecimiento de los

pueblos #marichuy #firmaporlavisibilidaddelospueblosindígenas #nuestraluchaesporlavidasembremosueñosycosechemosesperanza

[11] Disponible en: https://www.facebook.com/lapiztola.stencil?ref=br_rs, (consultado el 4 de enero del 2018).

[12] Fonoteca del INAH, No morirán mis cantos, No. 36, Antología Volumen I, Homenaje a la

maestra Irene Vázquez Valle.

[13] Me voy lejos,/ a lejanas tierras,/ donde

yo pueda llorar/ mi desventura./ Me voy por ti,/ donde tú no sepas,/ sí

corazón./ Amorcito ven,/ consentido, consentido./ Corazón, flor,/ aquí lo

llevo/ dentro de mi alma,/ sí corazón.

[14] Sign for Chuy